Free Fiction

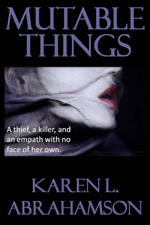

The second to last installment of Mutable Things is up today. Chapter 25 and 26 are Here.

The second to last installment of Mutable Things is up today. Chapter 25 and 26 are Here.

A Christmas Map of Place and Time

I put up the Christmas tree the other day, uncovering each tissue-wrapped ornament before putting it on the tree. My mother commented on how each one was so unique and that made me reflect on how each ornament was a memory that solidified and evoked a place that I had visited, or a certain place and time in my life.

I put up the Christmas tree the other day, uncovering each tissue-wrapped ornament before putting it on the tree. My mother commented on how each one was so unique and that made me reflect on how each ornament was a memory that solidified and evoked a place that I had visited, or a certain place and time in my life.

On the tree were ornaments purchased in Peru, and others from Tanzania, Cambodia, St.Thomas, and India. The tiny painted gourd Peruvian cuy (guinea pig), hung side by side with the wee silk elephant I found in Thailand. A German bauble my mother-in-law gave me hung next to a globe found at a French clock-maker’s shop at a town next to the Swiss border and a Pueblo Indian Virgin Mary sent by my parents from Arizona. All of these brought back memories of Christmas eve feasts, times in the Angkor heat or the chill of the Himalayas, and standing on the Serengeti plains.

Two of the dearest decorations were a handmade snowman and a tiny wooden cuckoo clock. The cuckoo reminds me of times with my stepsons and ex- husband out riding the wilds of Central British Columbia. You see, that area is ranching country complete with wolves and bears and miles of undeveloped forest. In the winter it was covered with snow-laden pine and spruce. At Christmas, there was no better way to start the season than to saddle up our horses and head out into that pristine winter land.

husband out riding the wilds of Central British Columbia. You see, that area is ranching country complete with wolves and bears and miles of undeveloped forest. In the winter it was covered with snow-laden pine and spruce. At Christmas, there was no better way to start the season than to saddle up our horses and head out into that pristine winter land.

We’d take an axe and an old horse blanket with us and head out into the forest, the horses blowing steam through their nostrils as they bounded through hock-deep snow, my sons rosy-cheeked as they raced their horses ahead until they came whooping back to announce that had found the PERFECT tree. That was what the ride was all about. We’d follow them – usually out to some clearing where a smaller tree would stand. My husband would dismount and shake the snow off, getting it all over himself and then, as a family, we’d critique the tree they’d found. If it passed muster, we’d chop the tree down, wrap it in the blanket and tether the blanketed tree to the horn of one saddle before starting our (much slower) ride home dragging the tree behind us. That would bring the official tree into our home and the small cuckoo clock was one of the first ornaments we bought as a family.

The snowman ornament was made by my youngest stepson. We didn’t have a lot of money in those days – at least not for ornaments for the tree – so he and I set out to make some. I still have the small green felt tree I made, but his is special: a stuffed white snowman complete with scarf, and broom and a black top hat all carefully sewn by ten-year-old hands. I smile and think of him, long grown to a man, whenever I find it each year.

And so my Christmas tree today is a guardian of riches worth more than the presents under it. Those glittering branches hold not only my memories, but also a map of the treasures of my life.

And so my Christmas tree today is a guardian of riches worth more than the presents under it. Those glittering branches hold not only my memories, but also a map of the treasures of my life.

Merry Christmas.

Free Fiction

Chapters 23 and 24 of Mutable Things are now available here.

Chapters 23 and 24 of Mutable Things are now available here.

New Years Giveaway

To celebrate the new year I’m giving away five print copies of my Fantasy YA, Terra Incognita. To put your name in for the draw, go to Goodreads here.

To celebrate the new year I’m giving away five print copies of my Fantasy YA, Terra Incognita. To put your name in for the draw, go to Goodreads here.

Spy Lands –Who really discovered the coasts of America

I mentioned last week about spies and maps and government subterfuge as aspects of maps that we rarely think about. Municipal governments still fool residents with streets on maps that are planned, but haven’t been built. Map makers take liberties with place names and add imaginary towns and streets that reflect their biases for and against university football teams. But in the past spies were frequently involved in cartographic subterfuge.

For instance, most of us were schooled that Captain Cook was the first European to lay eyes on the north western coast of North America. However there is mounting evidence that the English privateer (government sanctioned pirate) Sir Francis Drake, not Cook, first saw the coast of Oregon, Washington and British Columbia between 1577 and 1580 – 160 years before Cook’s journey.

Why isn’t this known?

First of all because some historians are hard pressed to let go of old ideas, but second of all because Drake’s journey was likely suppressed and evidence of it hidden, because of disputes with the Spanish that were, later, going to erupt into war. Drake is confirmed to have travelled as far north as Mendocino, California, the farthest north the Spanish had been, but a 412 year old map commemorating Drakes circumnavigation of the globe shows details of the coast of British Columbia that no one could have known unless they had been there. Additionally, archeological evidence – 1571 British coins and equipment – have been found in Oregon and Victoria, B.C. gardens, so that Drake is believed to have travelled as far north as Prince of Wales Island in Alaska. Finally, Drake’s cousin confessed under torture to the Spanish, that a fabled North Pacific island, Nova Albion, had been discovered by Drake and claimed for England 29 years before Samuel Champlain founded Quebec and before there was a Virginia on any map. This is believed to have been Vancouver Island, kept secret.

A further example of cartographic spies, deals with those icons, Christopher Columbus and John Cabot. Columbus, we’re taught, discovered the Americas while looking for China. Cabot’s fame is due to his first North American landfall by a European. Or at least that’s what we’re taught. But in a 1498 letter that was penned just months after Cabot’s historic return from Newfoundland, a spy in England wrote to Columbus and talked about earlier voyages by men from Bristol to the same place Cabot had been and that these earlier voyages had been to an “Island of Brasil” and that Cabot’s landfall “is believed to be the mainland that the men from Bristol found”. The spy’s letter also mentions that these voyages from Bristol were well known to Columbus – something that is further supported because Columbus had spent time in Bristol and Iceland in the 1470s – almost 20 years before he managed to convince the Spanish monarchy to fund his explorations. Did Columbus use this knowledge to convince Isabella? Did he use it to calm his crew on his long crossing?

A further example of cartographic spies, deals with those icons, Christopher Columbus and John Cabot. Columbus, we’re taught, discovered the Americas while looking for China. Cabot’s fame is due to his first North American landfall by a European. Or at least that’s what we’re taught. But in a 1498 letter that was penned just months after Cabot’s historic return from Newfoundland, a spy in England wrote to Columbus and talked about earlier voyages by men from Bristol to the same place Cabot had been and that these earlier voyages had been to an “Island of Brasil” and that Cabot’s landfall “is believed to be the mainland that the men from Bristol found”. The spy’s letter also mentions that these voyages from Bristol were well known to Columbus – something that is further supported because Columbus had spent time in Bristol and Iceland in the 1470s – almost 20 years before he managed to convince the Spanish monarchy to fund his explorations. Did Columbus use this knowledge to convince Isabella? Did he use it to calm his crew on his long crossing?

We may never know, and even if we do, will it matter? For Columbus IS an icon that history won’t forget, but what this shows is how secrets and spies permeate the European history of maps, so that who really ‘discovered’ the coasts of America may never be known. Of course, just talk to a First Nations/Native American person and they’ll tell you we’ve got it all wrong anyway. North America had been ‘discovered’ long before any European left home.

We may never know, and even if we do, will it matter? For Columbus IS an icon that history won’t forget, but what this shows is how secrets and spies permeate the European history of maps, so that who really ‘discovered’ the coasts of America may never be known. Of course, just talk to a First Nations/Native American person and they’ll tell you we’ve got it all wrong anyway. North America had been ‘discovered’ long before any European left home.

Free Fiction

Jaymee and David’s saga continues. To read Chapter 21 and 22, click here.

Jaymee and David’s saga continues. To read Chapter 21 and 22, click here.

The Place That Wasn’t There

I fell off the map this week – at least that was what it felt like when I learned that I’d been removed from the intercom list at my townhouse complex. It doesn’t sound like much – a simple omission when they were doing the complex list – but think about it. To the outside world I no longer existed in this location. I inhabited an invisible place outside of the normal world that happened to be located between the house number below me and the one above – much like the safe house in Harry Potter but without the overt magic. I was gone, and so was my home and all the mementos I’ve collected from across the world. And of course my cats.

I’ve experienced something similar before, when I worked in the interior of British Columbia in a small town that was a long ways away from anywhere. When my agency’s reporting relationship shifted from one region to another, all the paperwork connections seemed to disappear and no one contacted us – it was actually quite a nice change. But it was also like we inhabited some huge fog bank that filled a space in the center of the province that no one knew existed. Our own personal twilight zone.

Such phenomena isn’t only in my imagination. Cartographers have been erasing or omitting bits of the landscape from their maps since before Prince Henry, when choice harbors and trade routes were secrets worth killing for. In order to gain a truer picture of the world, it became common practice for Kings to confiscate the log books and charts of each ship that came to harbor in order to copy them down before the sailors took ship again.

During the time of the early Portuguese spice trade, the location of, the Moluccas, the five tiny islands that were the sole source of nutmeg, mace and cloves, were closely guarded secrets. True maps of the eastern Indian Ocean were treated as highly classified documents (and few exist today) due to the possibility that the Portuguese were violating a Papal bull which gave the Spanish sovereignty over all lands west of a longitudinal line running 100 leagues west of the Cape Verde Islands (in the Atlantic).

During the age of exploration and when Spain, France and England were vying for the Americas and the Northwest Passage, maps were made that purposely misrepresented the landscape in case they fell into (and sometimes purposely intended for) the enemies’ hands. Such maps were intended to deter exploration by competitor nations because the harbor, the river, the inhabitable, productive land wasn’t there.

Even today we see maps shift reality so that places exist differently than what you would find ‘if you were on the ground’. Road maps often include streets that are planned, but have never been built, or don’t describe that the street crossing that looks so direct on the map, can’t be made. A recent internet report showed that Chinese government maps of cities often change the position of major streets. Why? For military purposes. The government has apparently fallen back on the ancient practice of redrawing reality to stop potential invasion or intelligence gathering.

Happily, I’ve been replaced on the list of existing residents of my complex and so my home and I have been returned to reality. There is no longer a fog where my house once stood and my cats and I are all okay.

Free Fiction

Free Fiction brings bleak times for Jaymee and David. Chapters 19 and 20 are up here.

Free Fiction brings bleak times for Jaymee and David. Chapters 19 and 20 are up here.

The Roots of the World

For men like Fra Mauro (see last post), the exploration of the external world led to an understanding of the inner landscape of men. So too, from the triangulation of the world (see post here) came a greater understanding of the internal shape of the earth.

I mentioned previously that in order to determine the shape of the world, a French survey team went to Ecuador and Peru at the same time as a team went to Lapland. Unfortunately for the Peruvian team, the Lapland team discovered the answer to the scientific question long before the Peruvian team ever finished their survey. While in South America, however, the Peruvian team struggled over mountains and through jungles and noted different gravity readings as they took their survey measurements along their route. They surmised that the differences in the readings might reflect the varying landscape and theorized that mountains might be made of less dense material than the lowlands. A good theory, but it took over a hundred years for the matter to be more fully explored and the discovery was made far from South America. It took the British Raj’s need to survey India to bring understanding to what the mass of mountains might mean.

In the mid nineteenth century, the horrendous task of surveying India through triangulation was almost undone by the discovery of an error of some 150 meters between the distance the triangulation measurements computed, and an actual direct surface measurement. To determine what had led to the error, the cartographers involved had to reexamine their assumptions – in this case they had assumed that the mass of the Himalayan Mountains would greatly influence the gravity measurements of their survey instruments. What they found was that they had overestimated the lower mass of the mountains.

This led to a theory of the earth’s crust that still exists today, namely that every (theoretical) column of the earth (from core to outer surface following a theoretical plum line) should have approximately the same mass. Given that tall mountains have a lower mass, they must have an equally large (but low mass) protuberance at the bottom of the earth’s crust to achieve the same mass as denser areas of the earth’s crust. Conversely, under the oceans where the ocean basins are very dense, the earth’s crust would be relatively thin. The theoretical result would be that inside the earth there would be a mirroring of the plains, mountains and ocean valleys we see on the surface, much like a tall iceberg has a large underwater presence to balance it out. Modern science has supported this, by obtaining crust measurements off the coast of South America that show the Andes have roots as deep as 75 kilometers.

Think of this the next time you are crossing the mountains, staring up at those tall, snow-covered peaks, for they are the frosting, the outer conceit of an iceberg of stone that conceals the deeper reality of the roots of the mountains.

Much like Fra Mauro saw the illusions of men obscure the truth of his map of the world.