Rhumb Lines, Novel Writing and How to get from point A to Point B

As I mentioned in a previous post, I’m in the midst of a year of writing sequels. Actually it may take two or three years to get through all the sequels needed for my current novels. As I have already mentioned on this blog I’ve found writing my first sequel a bit of a challenge even though I knew where I was going. It seemed that I kept straying off course.

This puts me in mind of the challenges mariners had back before Gerard Mercator created his famous projection in 1569. A projection is a way of taking three dimensional landforms off of a globe and placing them onto a flat surface (a map) while retaining relative conformity of shape and relation between the landforms. What Mercator did was take meridians of latitude and longitude and make them all aim straight north-south or east-west creating 90 degree angles at each intersection. Sure it expanded the landforms closer to the poles, but it also gave mariners a means of plotting courses over long distances.

You see, prior to Mercator, mariners shared two fears – bad weather and getting lost. (Actually I share their fears, the latter most particularly when I’m writing.) In the years before Mercator’s projection, mariners had generally confined their sailing to the Mediterranean and coastal waters. The transatlantic voyages to America were done by the stars, but there were no helpful portolano (mariners maps using compass roses to show sailing routes) of the great oceans. Mercator’s grid made sailing the open ocean as easy as sailing the coasts because it gave sailors a means to chart a straight line (a rhumb line) from Point A to Point B across the ocean. From this they could plan their headings and make their voyages.

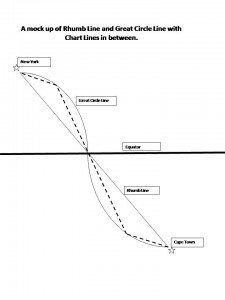

Of course sailing the distance from Cape Town to New York is about as huge an endeavor as writing a novel (or a sequel) from page one to the end and neither route actually takes a straight line. Sailors travelling that distance recognized that they didn’t travel a flat earth, they travelled a globe and so they added to their calculations, the curve of a great circle that was the largest circle they could draw through a sphere and this route showed the actual shortest distance between two points. Sailors then chose their routes by drawing straight chart lines between the great circle and rhumb line that allowed them to approximate the great circle along the route.

This seems a lot like the process I use when I’m writing. I know where I start and I know where I want to finish (most of the time). The writing process then becomes one of deciding how far to travel from the rhumb line (the plot or the backbone) of the story, for it seems to me that novels have great circles, too. These are the themes you are writing about and you don’t want to allow your plots to take over, so that your story is nothing but plot, but neither do you want your subplots to take you so far out of your way that the story no longer fits within its themes. And that’s where sailing and writing diverge in their process. Sailors use the great circles and rhumb lines to plot their course and they follow it from Point A to Point B. A writer, on the other hand, will use them to plan their novel or their series of novels, but also to look behind and check whether they have wandered too far off course to get to their final destination. This is the challenge in sequels: viewing the second or third book as just one of the charted lines between the rhumb and the great circle, building its way to the ultimate end of the voyage.