“A Good Traveler (or writer) has no Fixed Plans…”

I purchased a lovely journal the other day. Though it’s not specifically a travel journal it certainly could be, because all of the quotes in the book relate to travelling, but when I read the complete quote by Lao-Tzu, all I could think of was its applicability to writing. The quote goes thus:

‘A good traveler has no fixed plans and is not intent on arriving.’

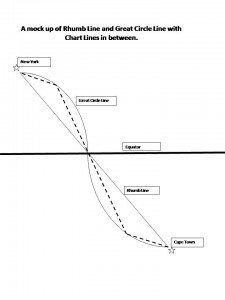

As someone who loves to travel, this quote provides a cautionary tale, because it warns that if you focus always on the destination you miss a lot along the way. Personally, I prefer to meander from place to place because you never know when you are going to find some better place to go than the place you intended. If you are always focused on heading somewhere, you have a much greater chance of missing where you are. As the Buddhists suggest, mindfulness of where we are, rather than worrying about the future (or where we are going) brings much more happiness than the rush, rush, rush of hurried travel. It’s for that reason that I don’t take bus tours. The tours point out what they think you want to know, not what you can really learn just by being there.

But Lao-Tzu’s quote applies equally to writing. The writer who spends all his/her time solely focused on completing a project isn’t really giving themselves the opportunity to enjoy the project. I’m not saying that you should fool around and never finish, I’m suggesting that you should enjoy the process, no matter how difficult it is, and—just like the traveler who takes the time to meander you don’t need to be so end-driven that you can’t enjoy the little sidepaths that your muse sends you down.

I guess what I’m talking about is allowing the story to carry you along, just like the road can. You don’t have to know where you are going exactly, though you may have a vague idea that you would like things to end in a certain way. Some of my best days of writing are when I have allowed the story to carry me away from the story I had intended—those are the mornings I get up and rush to get writing again because I want to know what happens next. The funny thing is that if you allow the little digressions and flashes of insight to lead you, often the ending will turn out to be some place better than what you envisioned. Believe me, if the ending surprises you, it’s going to surprise and charm your reader, too.

So as a recovering ‘plotter’ of novels I think all novelist should allow themselves the freedom to step off the path they are following to explore the new world they’ve created. They might just find it’s bigger and better than they ever imagined.